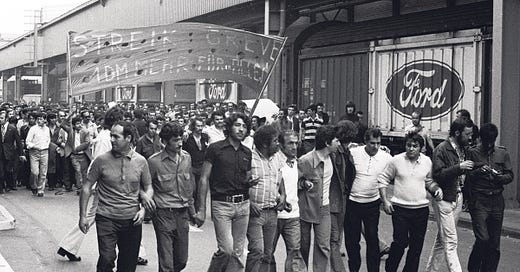

The 1973 Wildcat at Ford Cologne

A labor action by Turkish workers as pivotal event in post-war West Germany

This article originally appeared in Germany in the Winter 2003/2004 issue of Antifaschistisches Infoblatt. Some slight alterations have been made to reflect the passage of time since then.

August 2023 will mark the fiftieth anniversary of the work stoppage by Turkish immigrant workers at the Ford factory in Cologne-Niehl. This labor struggle, which in the meantime has become legendary, has repeatedly served in the last fifty years as an example and frame of reference for the resolution of social conflicts in the workplace with the broadest possible participation by "foreign colleagues." Furthermore, this labor struggle became an exemplar of a "wildcat strike", also against the will of both the DGB (the German Trade Union Confederation) and individual unions, in this case IG Metall.

the political treatment of the strike today - a brief outline

Knowledge concerning the concrete events and actors involved seems to be slowly vanishing behind all this - of course very truncated - reference to the Cologne strike . It's not surprising that commemoration of the strike was absent from the state and trade union 40th anniversary celebrations in 2001 of the German-Turkish recruitment agreement of 1961.

However, the radical left has also not offensively confronted the debate about these two emblematic dates in the history of the Federal Republic of Germany. In the context of the 40th anniversary of the German-Turkish recruitment agreement, the group 'kanak attack' attempted to convey the historical events around the Ford strike as an example of the self-confident struggle of Turkish immigrant workers for dignity - a concept that encompasses much more than "merely" the realization of social changes in the workplace. Furthermore, in the context of the Ford strike, 'kanak attack' raised the important question of the conditions of access to, and use of, the resources of "history, remembrance, and commemoration" for immigrants in the Federal Republic of Germany.

The date of the Ford Strike should also have a greater significance for the radical left because it points far beyond the concrete historical event. 1973 was also the year of the ban on the recruitment of foreign workers imposed by the German federal government. A new dimension of racist politics was thus initiated that increasingly regarded immigrants as a "problem." This viewpoint was already conspicuous in the contemporary media reporting on the Ford strike.

The strike - what actually happened?

The Cologne Ford strike was part of a nationwide movement of wildcat strikes between February and October of 1973 in which thousands of workers participated, the majority of them in the auto and steel industry. In a few workplaces, the strikes were in part brutally ended by the cooperation of police and plant security.

What was the strike, which occurred between August 24th and 30th 1973 on the Ford factory premises in Cologne-Niehl, about? The Cologne car manufacturer had employed Turkish workers since 1961. In 1973, with 12,000 employees, Turkish workers already constituted about a third of the entire workforce. Working conditions and wages for Turkish workers were bad and far below those of their German colleagues. 90 percent of Turkish workers were employed on the assembly line, many of them in the extremely labor-intensive finishing process. The immediate cause of the strike was the firing of about 300 Turkish workers in August 1973. The reason for their dismissal was returning late from vacation.

During an employee assembly a week before the strike, Turkish workers declared their solidarity with the fired workers, whereas the majority of German workers welcomed the firings, in part even demonstratively. They lacked understanding for the situation of the Turkish workers, who needed to use 10 days out of the four weeks of allotted vacation time in order to make a round trip to and from Turkey, and therefore only saw their families for about three weeks. Nonetheless, German workers participated - albeit hesitantly - in the strike. After Turkish colleagues agreed to take on the work of those who had returned late if the dismissals were withdrawn, a promise that the management of the Ford plant ultimately reneged on, on August 24 there were spontaneous work stoppages and demonstrations on the premises.

In general, it should be noted that during the entire strike, the strikers were present on the factory premises, and not, as was usually the rule with West German labor struggles, striking from home. The strike demands by Turkish workers that followed the work stoppage make clear that the non-retraction of the dismissals was only the endpoint of a development characterized by the continuous deterioration of the working conditions and wages of the Turkish part of the workforce. Among the demands, alongside the retraction of the dismissals, were 1 D-Mark more an hour, six weeks of paid vacation, a reduction in the speed of the assembly line, as well as the elimination of low-wage groups. The reaction of the plant management speaks for itself: management initially only promised to reconsider the dismissals, and held out the prospect of a one-time cost-of-living adjustment of 280 D-Mark, as a benefit for the entire workforce, however. The works council reacted with indifference. It bargained directly with factory management until Monday, August 27th, but was forced to recognize that it had no legitimacy anymore in the eyes of the strikers. The Turkish workers quickly took the strike into their own hands and named their own strike spokesmen. When it became clear to the works council and the IG Metall union that they could no longer channel the strike, they attempted to draw the German workers to their side with their own demonstrations, which actually succeeded. On Wednesday, August 29th, only German apprentices and temp workers were still striking with their Turkish colleagues.

Parallel to this, press reports began to change. Whereas initially the strike was characterized by some parts of the press as illegal but understandable, increasingly voices gained ground in the media that ethnicized the social protest. Suddenly, it was no longer about the speed of the line, but rather the "Turk problem" ("Türkenproblem") at Ford. The SPD-led state government of North Rhine-Westphalia did the rest as far as criminalizing the strike: interior minister Weyer announced on August 29th that the strikers were being observed by the criminal police and the Office for the Protection of the Constitution (Verfassungsschutz, the domestic German intelligence agency). Already the day before, federal chancellor Willy Brandt had asked the strikers to return "into the arms of the trade unions." Reinforced by the feeling of having public opinion on its side, plant management violently ended the strike after a week. Covered by a counter-demonstration of those "willing to work", police managed to gain access to the premises, and immediately began arresting the activists of the strike leadership. This action was flanked by the following headline in the tabloid newspaper Bild: "German Workers Fight to Reclaim Their Factory." As a consequence of the brutal smashing of the strike, over 100 Turkish workers were summarily dismissed; about 600 accepted the "offer" of turning the summary dismissal into a "voluntary resignation." The works council did not file a single grievance against any of the dismissals.

The Ford strike - what remains?

How is the strike now commemorated in retrospect? Already in a film about the strike by Thomas Giefer and Klaus Baumgarten from the year 1982 ("This work stoppage wasn't planned"; aired on the public television network WDR) the differing assessments of the strike are made clear. The strike is characterized from the viewpoint of the former strikers among other things as a "long defeat." The former speaker of the works council, Kuckelkorn, in contrast, admits in the film that the council did not provide adequate support for the strikers, but then claims that as a consequence of this inadequate support, the strike leaders, characterized as "agitators", had free reign. There is no mention of the treacherous role of the works council with regard to the Turkish colleagues. A conference on the Ford strike in November of 2001 organized by the "Network Migration in Europe" in cooperation with the IG Metall Cologne also demonstrated how contemporary witnesses in particular from the union context are still massively influenced by the institution "trade union" in their evaluation of the events of 1973. Here as well, the inglorious role of the works council and IG Metall is mainly ignored. The commemorative images of the strike are primarily shaped and formed by the union side.

The fact that Turkish workers who had participated in the strike were only able to speak at the margins of the conference leads back in an exemplary way to the question formulated at the beginning of this essay about the difficult conditions for establishing a commemoration of political struggles by immigrants in the Federal Republic of Germany. For example: in the summer of 2001, the first volume of the three-volume "German Commemorative Culture" was presented with great fanfare in Berlin. In this comprehensive collection of "places of remembrance", one encounters a chapter on "flight and displacement", but not a chapter on labor migration in the Federal Republic. The book presents an ethnically homogeneous culture of memory, in which the history of immigrants has no place and there are not even the rudiments of an assumption that labor migration in the Federal Republic has left behind traces of any form in the so-called "majority society." The book fits into attempts by the federal government of the time to establish a "national culture of remembrance. The Documentation Centre for Displacement, Expulsion, Reconciliation in Berlin that was established by that government is a manifest representation of such attempts.

What to do against this?

In recent years, the radical left has only inadequately understood "remembrance" as an important resource, as part of a counter-culture against state and everyday racism, to be brought into the public sphere against considerable political resistance, and made an impetus of activity in current political struggles. In order to advance the establishment of a commemoration of social and political struggles by immigrants in the Federal Republic of Germany, and putting it into action in current political struggles against social exploitation and racism, however, it's important to know what, for example, happened during the Ford strike. Furthermore, similar events should be rescued from oblivion, such as the actions of the "plakat" group around Mario d'Andrea and Willi Hoss at Daimler-Benz in the 1970s. The IG Metall, incidentally, also played a very infamous role in that regard.